By Zoya Khan

In 2010, a series of protests began across Egypt and Tunisia, known as the Arab Spring uprisings, leading to significant political changes throughout the Middle East and North Africa. The protests in Libya began in February 2011, resulting in the violent overthrow of Colonel Gaddafi’s regime. This insight argues that the transition from peaceful demonstrations to violent civil war in Libya had more to do with the role of external actors rather than internal factors.

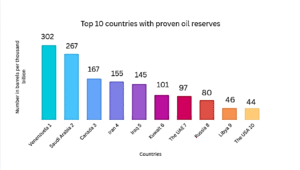

Libya, the fourth-largest country in Africa and the 16th largest in the world, is known for its vast desert terrain. It holds the largest oil reserves in Africa, ranking 9th globally with approximately 46.4 billion barrels, accounting for around 3% of the world’s proven oil reserves (Graph1).

Graph 1: Country Analysis Brief: Libya

Libya gained its independence from Italy in 1951, with King Idris I as its first ruler. Colonel Muamma r Gaddafi overthrew the monarchy in 1969 and established a socialist model of governance known as ‘Jamhariya’ or ‘rule of the masses’.

Source Britannica

Source Britannica

Colonel Gaddafi rejected Western-style democracy, adopting a political ideology that mixed socialism with nationalism. This approach allowed Libya to utilise its oil wealth for social welfare, infrastructure development, and enhanced living standards.

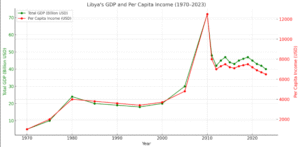

During Colonel Gaddafi’s four-decade rule, Libya underwent significant development, marked by increases in GDP and per capita income from the 1970s until 2000. Following 2000, a notable economic boom occurred, coinciding with China’s initiation of investments in Libya. By 2010, Libya’s GDP had grown to approximately $70 billion, with a per capita income of around $11,000 (Graph 2).

Therefore, the economic indicators imply that the uprisings against Colonel Gaddafi were not primarily caused by economic dissatisfaction, as living conditions and per capita income improved.

Graph 2: Country focus report Libya 2024

Source: (Self-Compiled)

As Libya’s economy improved, Colonel Gaddafi leveraged that wealth to extend his influence in Africa through pan-African and pan-Arab nationalism. As a major financier and chairperson of the African Union in 2009/2010, he utilised economic aid to promote African unity and advocated for a “United States of Africa” to diminish Western influence. The West grew concerned over Colonel Gaddafi’s efforts to establish an African central bank with a gold-backed currency, which threatened to reduce Africa’s reliance on the US dollar, the IMF, and the African-French Franc, thereby challenging Western dominance.

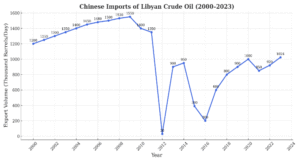

Traditionally, Western nations were the primary importers of Libyan oil, with the country exporting around 1.6 million barrels per day (bpd) to Europe. Italy and France were particularly dependent, as Libyan crude accounted for more than 20% of Italy’s total oil imports. However, under Colonel Gaddafi, Libya gradually deepened its ties with China. This expanding partnership with China, together with Colonel Gaddafi’s policy of resource nationalism, tightened contract conditions for Western nations to reduce their influence in Libya. These two factors jointly alarmed the West, which ultimately viewed this as a direct threat to its long-standing economic and strategic interests in Libya.

By 2010, China was importing approximately 150,000 (bpd) from Libya and had secured more than US$18 billion in infrastructure and oil projects (Graph 3). This deepening alignment with Beijing threatened the established position of Western states as major oil importers.

Graph 3: Trading Economics

Source: (Self-Compiled)

Given these Western concerns over Gaddafi’s growing independence and ties with China, the eruption of Arab Spring protests in 2010–2011 provided an opportunity for foreign actors to pursue regime change in Libya. Inspired by the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, Libyan demonstrations initially began as a small and largely leaderless movement calling for greater political representation. However, external involvement quickly altered the trajectory of protests. Support from the US, UK, France, Italy, Qatar, and Kuwait encouraged army defections, transforming protests into an organised rebellion under the National Transitional Council (NTC). This council soon became the political face of the opposition, backed by substantial foreign aid: the US allocated $25 million, Italy pledged $586 million, France $420 million, Kuwait $180 million, while Qatar delivered more than 20,000 tons of weapons.

The US, UK, and France called for UN involvement, resulting in the adoption of Resolutions 1970 and 1973, which authorised NATO to enforce a no-fly zone and protect civilians, while China and Russia abstained to uphold the principle of non-interference.

From March to October 2011, NATO conducted approximately 26,500 sorties and 7,000 airstrikes, significantly damaging military infrastructure and allowing the rebels to advance. Tripoli fell to the rebels, led by Mustafa Abdul Jalil of the NTC, and in October 2011, Colonel Gaddafi was killed. The conflict resulted in around 15,000 deaths and 45,000 injuries, and chaos continues in Libya to this day.

Colonel Gaddafi’s regime change by foreign involvement has both political and economic repercussions. Economically, the situation in Libya deteriorated after the fall of Colonel Gaddafi’s regime. By 2010, Libya’s annual oil production was steadily increasing, reaching above 1.3 million bpd. However, following the regime change in 2011, oil production sharply decreased to just 350,000 bpd and has never returned to the steady growth levels experienced during Colonel Gaddafi’s rule .

The political implications of Libya’s regime change have been severe, leaving the country fractured with transitional governments and parallel administrations claiming legitimacy.

Following the fall of Colonel Gaddafi in 2011, the NTC established a temporary government. In 2012, elections were held, and two parties claimed victory: the General National Congress (GNC) and the House of Representatives (HoR), resulting in a split of Libya.

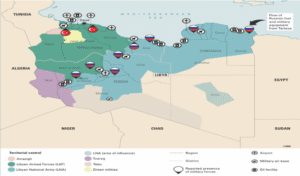

There are currently two governments in Libya. The Government of National Unity (GNU), based in Tripoli and led by Abdul Hamid Dbeibah, is a UN-recognised entity and is supported by Western states, Qatar, Turkey, and the Libyan Armed Forces (LAF). The Government of National Stability (GNS), led by Osama Hammad in Sirte, is backed by General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA). GNS is supported by Egypt, the UAE, and Russia (Map 1). Thus, Libya is fragmented, with various regimes controlling different areas, and there is no nationwide government.

Map 1: Foreign Military Presence in Libya

Source: (IISS Strategic Dossier)

The so-called Arab Spring uprisings in Libya were significantly shaped by foreign actors, extending beyond purely domestic grievances. Similar dynamics unfolded in other Middle Eastern and North African states such as Tunisia, Egypt, and Sudan, where internal challenges were intensified by external interference, resulting in prolonged instability. This pattern of foreign involvement reflects broader great-power rivalries playing out across the region.

Email: balochzoya9887@gmail.com